Friday and Saturday, Stephan Günzel (University of Potsdam) and Espen Aarseth (IT University of Copenhagen) hosted Ludotopia, a “Workshop on Spaces, Places and Territories in Computer Games”-. The workshop took place at the ITU with participants from Germany, Denmark, Norway, the UK, the US, and the Netherlands.

We had two great days of stimulating discussion. and here’s a few notes from ongoing work in game scholarship dealing with spatial issues in a wide variety of ways. CAVEATS: The notes are indicative of interests and approaches of the workshop participants, and do no fully sum up arguments or indeed scope of work (most of which is in progress). Please note that the notes are also personal (my interests and opinions are showing here and there).

[A FINAL NOTE: after writing this I realised it has turned into a general summary of the workshop. Let me point out that there's something on the interplay of virtual worlds and the real world (a core interest of the project), from LUDOFORMING and down + ending of the post].

Computer games present space in many different ways. In a influential paper [pdf], Espen Aarseth showed that “computer games can be classified by their implementation of spatial representation” but then went on to admit that “[a] thorough classification [...] would need much more detailed analysis”. Stephan Günzel’s presentation was an answer to that call for more detailed analysis.

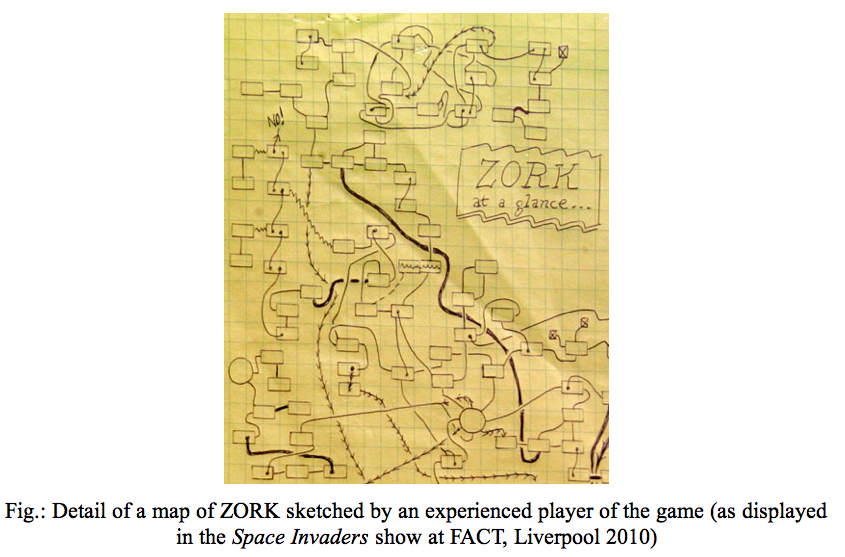

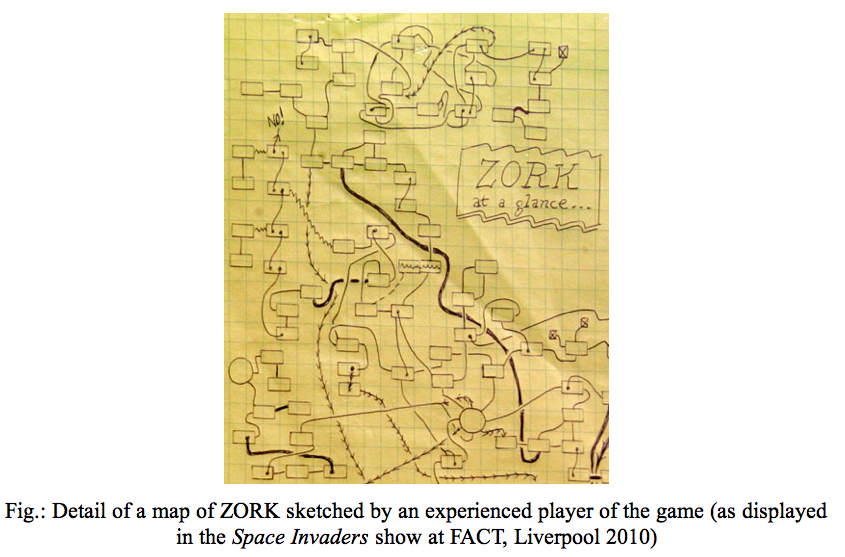

Günzel approached the plurality of representations through Nelson Goodman’s concept of “exemplification” (one kind of representation, as opposed to “denotation”), and described computer games as exemplifications of theories of space, or “truths of space”. I liked the approach for bracketing the empirical player’s experience completely (avoiding making claims as to the empirical player’s state of mind). Overview of the philosophy of space – with a refreshing German slant; must admit I’m only vaguely aware of the work of Karl Jaspers and afraid I never heard of Kurt Lewin – was combined with overview of computer game forms. Lewin’s “hodological space” is thus exemplified by “Mirror’s Edge” (below), relational space by “Zork”, etc.

One comes out from such a dip into the philosophy of space (and this was just a dip, I’m looking forward to a full splash) with sharpened attention to the wide range of possibilities inherent in screen-based, digital media (Günzel stresses the “video” in “video games”). Karla Höss‘ work was (also) stimulated by games that go beyond (or against, depending on your politics) “standard” 3D-simulation, e.g., Echochrome (click the film and/or see below) where the game playfully contradicts how perceptual depth cues function in the real world.

Whereas Höss’s fascination with computer game spaces could be said to be based in the perceptual (and in art history, btw.), Souvik Mukherjee’s fascination with computer game spaces had a cultural dimension, starting with the recent popularity of games set in (post-apocalyptic) waste lands. Those games were approached through Marc Augé’s non-place concept – but Deleuzian “any-space-whatever” turned out to work better. (Computer games and the philosophy of space: a fitting combination indeed.)

One of Mukherjee’s waste lands was that of “S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl”, a game that also caught the eye of Espen Aarseth because it provided him with an example of what he calls “ludoforming”, after “terraforming”. Wkipedia has an impressively solid article on terraforming, starting with the following definition “the hypothetical process of deliberately modifying [a planet, moon, or other body's] atmosphere, temperature, surface topography or ecology to be similar to those of Earth to make it habitable by terran organisms.”

Aarseth defines ludoforming as the “editing [of] an existing [i.e., real-life] topography to fit the ludic topology”. An example would be the way in which Chernobyl’s real-life topograhpy (to be associated with the sign-stream, or expression level, or semiotics of the game) is changed to fit the game’s topology (the “room-for-movement through which the player’s token navigates”). Incidentally, Jim Rossignol has blogged about “S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl”, with special attention to the importation of textures from RL to VW (with the aid of photography). Here’s a couple of pictures from that post, showing a RL “antenna wall – actually an early-warning radar system developed for Cold War defense” and the “brain scorcher” it inspired (inside the game, that is).

Aarseth’s presentation had a certain affinity with that of Michael Nitsche. Nitsche is interested in the ways “fictional video game spaces can transform “outwards”" – Nitsche’s focus was on “outwards” transformation “[redefining] our living rooms and ultimately our understanding of physical space as such” – and the practice of ludoforming is, arguably, indication of a certain “game gaze” (Aarseth’s term) on the world. (It is crucial, I believe, to distinguish clearly between Nitsche’s “understanding of physical space as such” (explicitly about how an empirical player actually perceives spaces) and Günzel’s “exemplifications” of “truths of space” (explicitly about theories of space, bracketing actual player experience).)

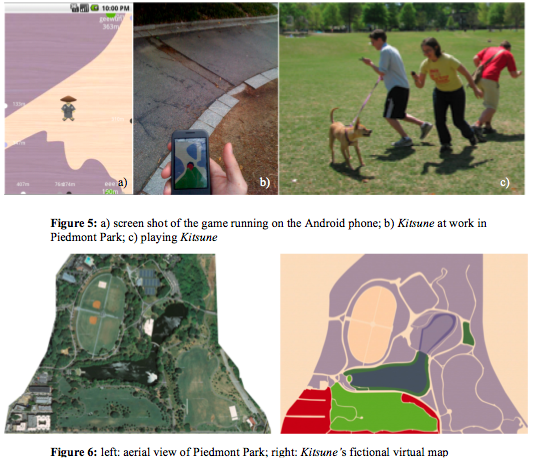

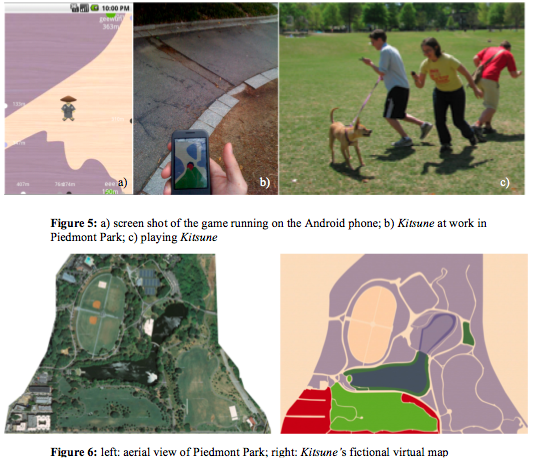

Whereas Aarseth deals with editing of the real world, or “optimisation” for ludic purposes in Nitsche’s view, Nitsche himself focuses on “inclusion” of the real world, and the “adding on to” the real world. His work is part of the Next Generation Play project that aims at realising the “convergence between established media, such as television and print, and locative social media such as cell phones”, e.g., Andrew Robert’s (a student of Nitsche’s) location-based “Kitsune” game:

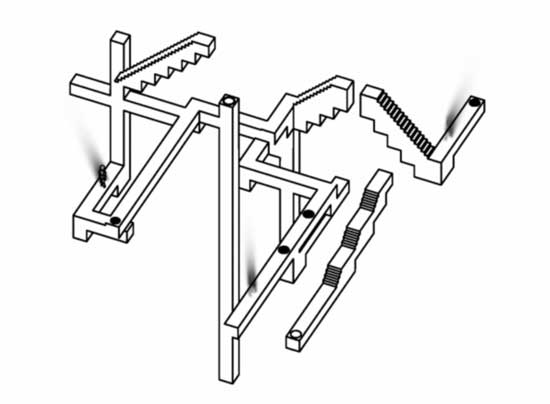

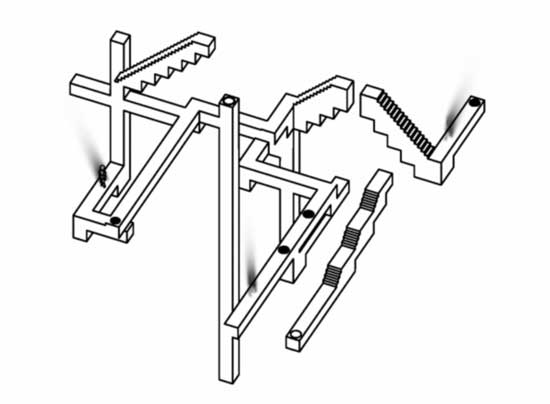

On a methodological level, also Alison Gazzard’s work is informed by a blending of RL and VW, with her fine-grain morphology (or topology, depending on your terminology) of the structures allowing movement in game spaces (tracks/paths, gates, bridges, loop-backs, loop-alongs etc.) informed by field studies of RL mazes (e.g., the one depicted below).

My own presentation also hinged on structures – “structures” in a specific sense taken from architectural theory. My point was that the special-purpose cartography performed by players of game worlds such as “World of Warcraft” is aimed at explicating, and attuning oneself to, structural flows of transportation, resource gathering etc., and that such cartography is indicative of what the virtual world “is” in the mind of the player. The 2D maps and the 3D spaces on screen are “renderings of the same f***ing thing”, as Nitsche concisely summed up my argument.

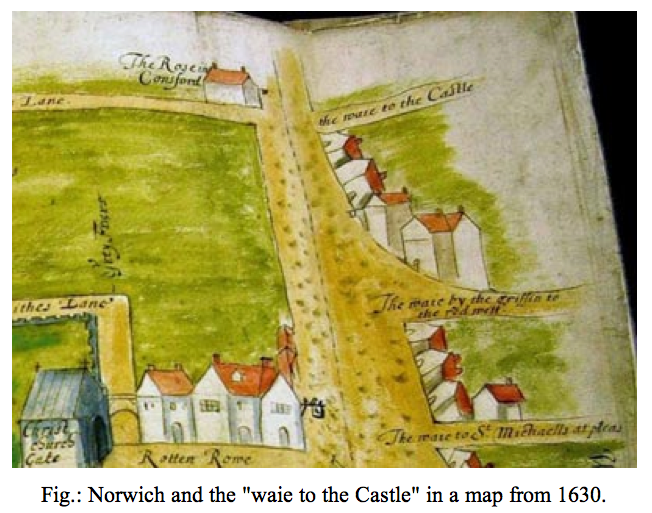

That f***ing thing that is rendered, the “world”, is something related to but quite different from “space” (guess Henri Lefebvre [who showed up repeatedly throughout the workshop] would boiled it down to the difference between “perceived space” and “lived space”). Or as the history of cartography teaches us, according to Denis Cosgrove who has written on this on several occasions, maps (and landscape paintings, Edward S. Casey might add) have not always, and do not always, aim at representing the Earth, but the World.

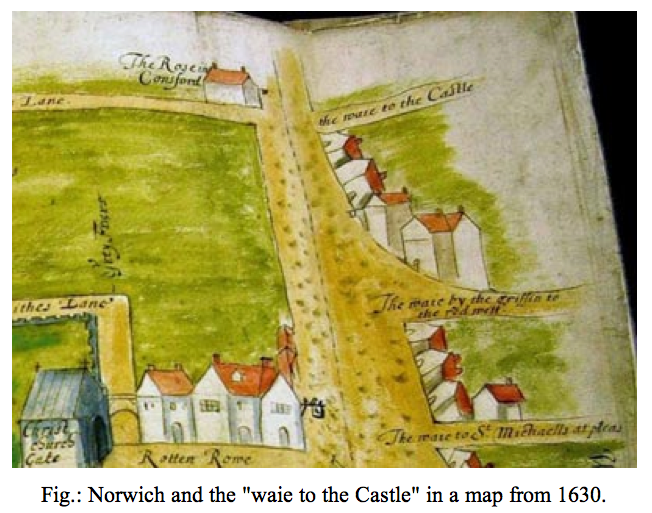

Mathias Fuchs presented a rich sample of cartography from RL and VWs, good for contemplating the difference between earth and world (Fuchs himself focused on the interplay of text and image):

The concept of “world” did not come up much in the workshop, but I believe it lurked under the surface of Sebastian Möring’s stab at a definition of “play space”. Applying Heidgger’s thinking on fear, Möring touched on the “[player's fearing] for his being in the game”. Here “game” is of course relatable to both “space” and “world” but perhaps more so to “world”. (That’s probably how Olli Leino would look at it. His recent PhD thesis was opposed a space-centric approach and dealt with [amongst other things] the possibility of being expelled from the “game world”. Btw., Leino didn’t touch Heidegger at all, but based his work in Sartre.)

Niklas Schrape’s approach to computer game spaces was a rhetorical one (main theoretical framwork: Lotman), arguing for the game space being the basis for argumentation (not argumentation itself). In his main example, a critical analysis of Global Conflicts: Palestine, that basis for argumentation turned out to be an unproductive dichotomy which the game then cued its player to deconstruct.

Both Sebastian Domsch and Teun Dubbelman approached computer game spaces narratologically. Narrative space, as we know it from movies and literature, is not the continuous space we know from some computer games. Narratives, in other words, tend to cut up space – but that sentence is far from all there is to say about the relationship between narrative, game, and space. Taking space as their starting point, both Domsch and Dubbelman set out to explore narrative in games (and in spaces!) in ways that seem far more promising than the tired old game studies “rules vs. story” discussion.

The implementations and experimentations with 3D-modelling amongst the architects we have been interviewing for this project mirror some of the issues taken up at the Ludotopia workshop. The virtue (and the curse) of the architect’s digital 3D-model is its being a 1:1 model. It’s a 1:1 model because its has no scale (in the way a rendering such as a print/drawing has scale), and therefore in principle holds all information about a project. The architects’ task then becomes the editing and refining of a huge amount of data given at the outset of the project – as opposed to pre-digital pratice where the project would start out sketchy (containing very little data) and then accumlate data exponetially towards its completion.

Like most computer games with a weak, narrative dimension, the 1:1 model relies on continous space. Experimentations with “digital morphogenesis” (Branko Kolarevic’s and later Neil Leach’s umbrella term for “topological architecture” and other trends in architecture relying on digital simulation [mostly of processes found in nature]) can be seen as an attempt to brake away from reliance on continous space. A game such as “Echochrome” shares that slightly subversive, or at least creative, approach to spatial design. Attempts to involve users of the built environment in its design goes in the opposite direction, embracing instead of undermining the neutrality of the 1:1 model. When users are invited into VW version of the places their (are to) live in (or maybe even own), in order to create an authentic sense of “ownership”, that space has to be continous, also in the sense of narrative-free.

- Bjarke

Recent Comments