Gaming virtual worlds are becoming so ubiquitous that they are even appearing in the facebook social networking platform. What I provide below are some examples of these various social games. The question I would like to pose to our readers is this: Do these facebook apps qualify to be virtual worlds? And why or why not?

YoVille: In the first of what could be classifiable as true virtual worlds, YoVille is produced by app developer Zynga, the most profitable app developer on facebook. In YoVille you can decorate yourself and your house, buy items, send gifts to friends, visit friends, and play a variety of games. At one time, you could invest in the baking of cakes and cookies, where they could be produced over a certain time and then sold for profit. However, they have since reverted to rewarding bonuses for making an appearance at the Factory. In the first version, you could get drunk at the nightclub, making your screen go blurry, and you could encounter strangers to make new friends. In the beginning, the app would be crowded with people. Since then, you encounter fewer and fewer strangers, until now when you are only likely to encounter people you have already friended on Facebook.

YoVille: In the first of what could be classifiable as true virtual worlds, YoVille is produced by app developer Zynga, the most profitable app developer on facebook. In YoVille you can decorate yourself and your house, buy items, send gifts to friends, visit friends, and play a variety of games. At one time, you could invest in the baking of cakes and cookies, where they could be produced over a certain time and then sold for profit. However, they have since reverted to rewarding bonuses for making an appearance at the Factory. In the first version, you could get drunk at the nightclub, making your screen go blurry, and you could encounter strangers to make new friends. In the beginning, the app would be crowded with people. Since then, you encounter fewer and fewer strangers, until now when you are only likely to encounter people you have already friended on Facebook.

SmallWorlds: SmallWorlds is unique in that the potential true virtual world exists as a separate website: it is an in-browser virtual world that has created an app for users to access their account without leaving the facebook platform. In SmallWorlds, the user has more control over the customization of the avatar than s/he does in YoVille. Also, there is no production scheme integrated into the world; instead, the user gains money and experience by going on missions. As with YoVille, the user is given a house to decorate as a starting base. Consistent in SmallWorlds is the potential to make new friends via strangers; this is especially important as it is not as integrated into facebook as is YoVille, meaning that the friends list of facebook does not inform who one’s friends are in SmallWorlds.

SmallWorlds: SmallWorlds is unique in that the potential true virtual world exists as a separate website: it is an in-browser virtual world that has created an app for users to access their account without leaving the facebook platform. In SmallWorlds, the user has more control over the customization of the avatar than s/he does in YoVille. Also, there is no production scheme integrated into the world; instead, the user gains money and experience by going on missions. As with YoVille, the user is given a house to decorate as a starting base. Consistent in SmallWorlds is the potential to make new friends via strangers; this is especially important as it is not as integrated into facebook as is YoVille, meaning that the friends list of facebook does not inform who one’s friends are in SmallWorlds.

MiniPlanet: One of the newest arrivals to facebook, MiniPlanet seems to be a hybrid of YoVille and SmallWorlds. In appearance, the interface and graphics are very similar to SmallWorlds, but it is developed strictly as a facebook app. As YoVille experimented with, there is a production component to MiniPlanet, where each person has not only a house to customize but a store from which s/he can sell goods to earn money. As with the old YoVille, in MiniPlanet you have both facebook friends to socialize with, and there are places to chat with strangers to make new friends. As it is the newest of the three, there is not as much to do in the game; but given time, it has the potential for user-generation that SmallWorlds encourages, as does YoVille but to a lesser extent.

MiniPlanet: One of the newest arrivals to facebook, MiniPlanet seems to be a hybrid of YoVille and SmallWorlds. In appearance, the interface and graphics are very similar to SmallWorlds, but it is developed strictly as a facebook app. As YoVille experimented with, there is a production component to MiniPlanet, where each person has not only a house to customize but a store from which s/he can sell goods to earn money. As with the old YoVille, in MiniPlanet you have both facebook friends to socialize with, and there are places to chat with strangers to make new friends. As it is the newest of the three, there is not as much to do in the game; but given time, it has the potential for user-generation that SmallWorlds encourages, as does YoVille but to a lesser extent.

Pet Society: From another big apps developer, Playfish, Pet Society is one of the first social games on facebook to offer the user the ability to customize an avatar — in this case a cartoonish animal — decorate a domicile, and, by inviting and interacting with facebook friends, to increase in experience and the ability to buy items. Since it was first release, the game has become more complex, as more games and ways of earning money have been introduced, so that now the user can grow food in a garden and cook meals in a microwave, all for profit. However, there is no chat function as with the previous three games; there is an ability to make new friends via visiting strangers’ houses. As with YoVille, gifts can be sent to friends; unlike YoVille, this can only happen from inside the game.

Pet Society: From another big apps developer, Playfish, Pet Society is one of the first social games on facebook to offer the user the ability to customize an avatar — in this case a cartoonish animal — decorate a domicile, and, by inviting and interacting with facebook friends, to increase in experience and the ability to buy items. Since it was first release, the game has become more complex, as more games and ways of earning money have been introduced, so that now the user can grow food in a garden and cook meals in a microwave, all for profit. However, there is no chat function as with the previous three games; there is an ability to make new friends via visiting strangers’ houses. As with YoVille, gifts can be sent to friends; unlike YoVille, this can only happen from inside the game.

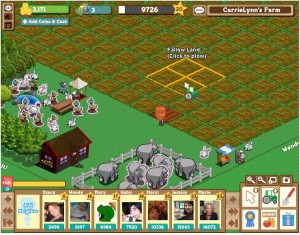

Farmvillle: The largest social game on facebook, with currently around 74 million active monthly users, this social game is the reason Zynga is the powerhouse of facebook app developers. Again the user can customize an avatar, but instead of a house, s/he is given a plot of virtual land to grow crops on. As it is from the makers of YoVille, the user can visit his/her facebook friends’ farms and perform chores for them, for which they receive money and experience. There is also the potential to chat with strangers in a marketplace as the user seeks help to tend to his/her farm. However, the socializing aspect is not as prevalent as in YoVille: the purpose of this game is the production of crops for leveling up.

Farmvillle: The largest social game on facebook, with currently around 74 million active monthly users, this social game is the reason Zynga is the powerhouse of facebook app developers. Again the user can customize an avatar, but instead of a house, s/he is given a plot of virtual land to grow crops on. As it is from the makers of YoVille, the user can visit his/her facebook friends’ farms and perform chores for them, for which they receive money and experience. There is also the potential to chat with strangers in a marketplace as the user seeks help to tend to his/her farm. However, the socializing aspect is not as prevalent as in YoVille: the purpose of this game is the production of crops for leveling up.

Country Story: Another entry from Playfish, Country Story is their attempt to make a farming social game like Farmville — a type of game that has the most copycats on facebook as various app developers attempt to replicate Zynga’s success. Country Story shares Farmville’s focus on the production of crops. However, it differs in a variety of ways. There is less of a community feel, especially as there is no in-game chat feature to meet other players. Instead, the user is given a variety of tasks, or missions, to complete, as one way to level up. S/he can visit facebook friends’ farms, and like with Farmville complete tasks for them; however, s/he can also steal their crops for his/her own personal game. As it is from the makers of PetSociety, it is more cartoonish, but it is also more of a fluid animation than Farmville. Unlike PetSociety, there is no way to visit strangers’ places and thus make new friends.

Country Story: Another entry from Playfish, Country Story is their attempt to make a farming social game like Farmville — a type of game that has the most copycats on facebook as various app developers attempt to replicate Zynga’s success. Country Story shares Farmville’s focus on the production of crops. However, it differs in a variety of ways. There is less of a community feel, especially as there is no in-game chat feature to meet other players. Instead, the user is given a variety of tasks, or missions, to complete, as one way to level up. S/he can visit facebook friends’ farms, and like with Farmville complete tasks for them; however, s/he can also steal their crops for his/her own personal game. As it is from the makers of PetSociety, it is more cartoonish, but it is also more of a fluid animation than Farmville. Unlike PetSociety, there is no way to visit strangers’ places and thus make new friends.

Restaurant City: Another entry from Playfish is the social game Restaurant City, apparently the first of a different type of social game. Rather than grow crops, the user is given a restaurant to make and sell food. The major customization of the game is the restaurant, which can be decorated with an ever increasing inventory of items and is expanded as the user levels up. Avatar creation is minimal, but the user can hire his/her friends to staff the restaurant, with the ability to give the staff uniforms. Money and experience are earned by serving customers. The user must balance the staff’s jobs by allocating who cooks food, serves food and cleans the restaurant. If a proper balance is not achieved, customers will not be satisfied; the more the customers are satisfied, the more customers the restaurant will get, and the more money and experience can be made. Thus, the user is not directly controlling the production of food; s/he is controlling the performance of his/her staff to keep the customers happy. After making decisions about menu and staff allocation, the user can sit back and watch what happens, making changes as s/he sees as needed — it is the digital equivalent to owning an ant farm. As with other Playfish games, the user can visit his/her friends’ restaurants to do chores, trade food, and send gifts. While the user can visit strangers’ restaurants, there is no way to interact with strangers, unlike in PetSociety.

Restaurant City: Another entry from Playfish is the social game Restaurant City, apparently the first of a different type of social game. Rather than grow crops, the user is given a restaurant to make and sell food. The major customization of the game is the restaurant, which can be decorated with an ever increasing inventory of items and is expanded as the user levels up. Avatar creation is minimal, but the user can hire his/her friends to staff the restaurant, with the ability to give the staff uniforms. Money and experience are earned by serving customers. The user must balance the staff’s jobs by allocating who cooks food, serves food and cleans the restaurant. If a proper balance is not achieved, customers will not be satisfied; the more the customers are satisfied, the more customers the restaurant will get, and the more money and experience can be made. Thus, the user is not directly controlling the production of food; s/he is controlling the performance of his/her staff to keep the customers happy. After making decisions about menu and staff allocation, the user can sit back and watch what happens, making changes as s/he sees as needed — it is the digital equivalent to owning an ant farm. As with other Playfish games, the user can visit his/her friends’ restaurants to do chores, trade food, and send gifts. While the user can visit strangers’ restaurants, there is no way to interact with strangers, unlike in PetSociety.

Cafe World: After Playfish released Restaurant City, their main competitor Zynga released Cafe World. Another of the restaurant apps, again avatar customization takes a backseat to restaurant decoration. As with Restaurant City, the user can hire his/her friends to be staff members. However, unlike the previous, in Cafe World all hired friends are automatically wait staff; the only cook is the user. The goal of the game is not to balance the staffing of the restaurant, but the creation and distribution of dishes. As the user levels up, more and more dishes become available on the menu, and each dish costs a specific amount to make, takes a specific amount of time to prepare, and will bring in a specific amount of profit. As with Restaurant City, friends’ restaurants can be visited and chores performed for reward, and again there is no means by which to contact strangers. This lack of in-game chatting makes Cafe World different from the other Zynga examples provided here.

Cafe World: After Playfish released Restaurant City, their main competitor Zynga released Cafe World. Another of the restaurant apps, again avatar customization takes a backseat to restaurant decoration. As with Restaurant City, the user can hire his/her friends to be staff members. However, unlike the previous, in Cafe World all hired friends are automatically wait staff; the only cook is the user. The goal of the game is not to balance the staffing of the restaurant, but the creation and distribution of dishes. As the user levels up, more and more dishes become available on the menu, and each dish costs a specific amount to make, takes a specific amount of time to prepare, and will bring in a specific amount of profit. As with Restaurant City, friends’ restaurants can be visited and chores performed for reward, and again there is no means by which to contact strangers. This lack of in-game chatting makes Cafe World different from the other Zynga examples provided here.

Home Inn: The final example here is a unique social game as I have not yet encountered another like it. Instead of having a farm or a restaurant, the user operates a hotel. There is customization of an avatar, but the main focus is the decoration and building of a multi-level hotel where each room is rented out to a friend or special guest for a specific period of time. While the guest is in residence, the user is expected to keep the room clean, keep the guest happy, and provide food. The happier the guest and the nicer the room, the more money and experience are rewarded. Food is produced in a kitchen using a method similar to that of Cafe World. As with all these games, the user is able to visit the hotels of friends to do chores for extra money and experience, as well as send gifts of decoration and food. Again, with the majority of these production-focused social games, there is no ability to visit non-friends’ hotels or engage in in-game chat.

Home Inn: The final example here is a unique social game as I have not yet encountered another like it. Instead of having a farm or a restaurant, the user operates a hotel. There is customization of an avatar, but the main focus is the decoration and building of a multi-level hotel where each room is rented out to a friend or special guest for a specific period of time. While the guest is in residence, the user is expected to keep the room clean, keep the guest happy, and provide food. The happier the guest and the nicer the room, the more money and experience are rewarded. Food is produced in a kitchen using a method similar to that of Cafe World. As with all these games, the user is able to visit the hotels of friends to do chores for extra money and experience, as well as send gifts of decoration and food. Again, with the majority of these production-focused social games, there is no ability to visit non-friends’ hotels or engage in in-game chat.

Across these examples we can see various facebook apps that have been developed on the basis of social gaming: of providing gaming opportunities for users to earn some virtual prizes by sharing the gaming experience with as many of their facebook friends as possible. In some ways, these are all virtual worlds because they are digital environments that people share, are represented in via avatars, and which, in some way, persist without their involvement, whether through production processes or the activities of other users. However, not all of these games involve worlds where users share the digital space concurrently. Especially in those worlds that are intended to be production-based social games, most communication with others occurs asynchronously, by visiting friends and sending them gifts and/or messages.

Also, regarding the issue of avatars, all games have a humanoid character representing the user to other players; at the same time, the house/farm/restaurant/hotel that the user customizes can also be considered as an extension of the user’s identity, as it is another way the user is represented inworld to other users. Of course, the majority of these representations are static and are not highly controlled moment-by-moment by the user — but the control of the system in Restaurant City does come close to producing a multiple entity avatar, similar to the relationship between game and user created in such games as SimCity.

Thus my question remains: are these facebook apps virtual worlds? If so, does that mean our definitions for virtual worlds need to be examined? If not, why not, and what do we call them?

Hi Carrie,

What a great overview!

Concerning your questions: I really think that we need to consider our use of the term virtual world to examine if it makes sense and if so how. The way I see it at the moment, an experiential approach to the questions that you ask is the approach which is the most interesting. Rather than defining it, I seek to understand what it is that creates the feeling of engaging with a world, if so.

One of the striking findings of my ongoing case studies of the virtual worlds of EverQuest and Second Life is that the participants do not refer to the concept of virtual worlds, that is, the general and abstract way of referring to the environment, rather they point at the meaningful places, the names of the games, their virtual land and projects. I’m not quite sure where that leads me, yet

Indeed, that interpretivist approach is something I have been thinking about, as there is a very subjective aspect for the definitions of virtual worlds that I have seen but that the authors of such definitions have not directly spoken to. The idea of what does it mean to sense that you are in this virtual world, that you sense it is a space/place and that there are other people there via their avatars. And also how much is this sense predicated or necessitated by digital technologies like synchronous communication, 3D graphics and naturalistic interfaces; when we consider text-based MUDs or the 2D asynchronous environments in these facebook apps, what matters more to people is not how they do something but what they do and why.

“Do these facebook apps qualify to be virtual worlds?”

Tateru Nino, massively.com, Jan 24, 2010: “The term ‘virtual world’ is slowly seeing less use, being supplanted by the more general ‘virtual environment’, but the world term still has a fair bit of life left in it….[]…Second Life, Blue Mars, There.com, IMVU and others trying to find places in non-game contexts, like content-development and prototyping, publishing and performance, entertainment and social, education and business; efforts that are met with varying amounts of success.”

It will be a big task to make people, and the media, used to call certain 3D spaces, virtual world and others virtual environment, if it ever happens.

I guess thats right, we are going to see a change of terminology, still, the reason why I dont use the term virtual environment is that it has been in-use for quite some time in the field of teaching and learning (VLE – Virtual Learning Environments); this is, however, not the reason why I still prefer to use Virtual Worlds rather, it is because the concept of environment is associated with the many CSCW and CSCL systems that generate no sense of being in a world. I think that the sense of being in a world, engaging with agencies in a world are important aspects that need be further researched. Also, some of the virtual worlds apps of your overview Carrie as i see them (and I have not tried them out) they are narrow in scope and scenarie, like a building, café, home in etc.; probably they would generate a sense of place but not of being in a world. Writing this I come to think of one of the participants of my video interviews – a young expert of mass role-playing games, Martin – who compares the simple and the more advanced games by pointing out the difference that in a simple game you get the sense of being in a confined space, almost like a lane or field, whereas in most advanced role-playing games there is this sense of a “whole world to be explored”.

rather, it is because the concept of environment is associated with the many CSCW and CSCL systems that generate no sense of being in a world. I think that the sense of being in a world, engaging with agencies in a world are important aspects that need be further researched. Also, some of the virtual worlds apps of your overview Carrie as i see them (and I have not tried them out) they are narrow in scope and scenarie, like a building, café, home in etc.; probably they would generate a sense of place but not of being in a world. Writing this I come to think of one of the participants of my video interviews – a young expert of mass role-playing games, Martin – who compares the simple and the more advanced games by pointing out the difference that in a simple game you get the sense of being in a confined space, almost like a lane or field, whereas in most advanced role-playing games there is this sense of a “whole world to be explored”.

Martin’s comment has me thinking back to over a year ago when I was sussing out the usage of “virtual worlds”. Because the World Wide Web itself gives me a sense of being able to explore the whole wide world, and these graphic spaces found in these games and elsewhere like Second Life are just specific places I can visit; they are not, however, the whole wide world. How can what researchers like Bell are trying to delineate as true “virtual worlds” be anything more than specific subsets of the possibility of the internet?

Of course, from a cosmological view, places like Second Life, with their inherent boundaries, are similar to our physical world which has specified boundaries and is different from other worlds like Venus or Mars. Perhaps then the internet is the universe (or to be even more philosophical, all of reality, as reality may contain multiple universes). In this view, these games on Facebook could be “virtual asteroids”…

My main point would be for the need of any definition of virtual worlds to account for the user’s perception or sense of the technology or space as a place, as being expansive, being persistent and being inhabited. It’s not just the design that is important in determining what something is or is not — the user plays a role in that determination, especially as it is ultimately the user who determines success/failure through their use or lack thereof

Sisse wrote: “Rather than defining it, I seek to understand what it is that creates the feeling of engaging with a world, if so.” I find this approach very intriguing.

I am reviewing Interface Fantasy: A Lacanian Cyborg Ontology ( André Nusselder 2009). This book takes a perspective on fantasy as an interface. I am quite content that Nusselder’s approach can add a new dimension to our understanding of how people engage with and perceive what is meditated through ICTs, as well as what creates the feeling of engaging with a world.

In relation to the tensions between the roles ascribed to technology, as either passive mediators (as mere extension of human needs and desires), or as sociotechnical ensembles of heterogeneous human and nonhuman actors, “Interface Fantasy” promises a new point of view from which to approach people’s engagement with ICT (which can also include virtual worlds). Whereas most STS – studies have focused on materiality, agency, and connections as key concepts, thereby treating the mediator as something outside the individual user, this book adds another dimension since cyberspace is perceived as a mental space, where fantasy as something internal mediates whatever is shared.

I think this can be interesting as the focus is not on the technology, (whether 3D or not) neither on the connections, (whether you are engaging with your Facebook friends or meet new ones), nor your representation (to which extend you qualify as an avatar). From this perspective focusing on presence, or sense of being in a world, becomes a matter of the individual and his/her experience.

This makes the question “Does Second life provide us with more presence or sense of being than Farmville?” uninteresting. As, instead, we focus on people’s ability to feel that they are in a particular world.

I recently interviewed a guy from a advertising agency asking why they did not focus on virtual worlds I their campaigns. He told me that he did not know how to relate to it. He described his first encounter as: meeting a woman, being introduced to one of her male friends, and, suddenly, finding himself in the middle of a sex game he did not understand. For him there was no sense of presence at all, his experience turned the virtual world into a very visible and confusing mediator.

Similarly Carie Heeter (“Reflections on Real Presence by a Virtual Person” 2003 p 336) argues that real presence is not only a matter of sensory realism and “real” stimuli. She illustrates this by her visit to the space shuttle Enterprise. Despite the total physical realism, she did not particularly feel that she was there, because her sense of presence was dampened by expectations, lack of familiarity, limited prior experience, and limited cognitive schemas.

So my suggestion would be to include a psychological perspective, defining virtual worlds not from the ways in which people can interact, are connected, or from their goals in the world (as in Carries description above), but instead from the sense of being present that people experience.

The one thing I would caution, Dina, is the “phenomenological trap” — where instead of ascribing causation for presence only to the technology, you would do the opposite and ascribe it as within only the user’s purview. Presence — or whatever other words you want to use to discuss that “sense of being there” — like many other phenomena, is a combination of cues/constraints of material reality and the interpretation of that material reality by the user. It is not a balancing game but a constant flow of back-and-forth and side-to-side and up-and-down and so forth. It is a process of engaging, and thus a complex one at that.

That’s why my suggestion was to *include* a psychological approach. Use is as yet another view that offers perspective and raises new questions. I did not see it as something that should replace the approaches that takes reception, networks, or human/nonhuman agents as their main points of interest.

Coming from an STS background usually my starting point is to capture dynamics as you mentioned. The psychological approach was just yet another dimension that I found interesting to throw it into the discussion.

That being said I find it fascinating to read different studies and see what (be it internal as I psychology, external, as in network analysis, or somewhere in-between) such approaches ascribe as important when defining virtual worlds or spaces.

farmville is the best game ever and this is the best blog post!

Just to note, virtual world Habbo is also on Facebook, with various versions of its Habbo Hotel, such as this one, the Habbo Hotel UK: http://www.facebook.com/apps/application.php?id=140597994210. As with Small Worlds, here is a browser-based virtual world / social game that exists outside of Facebook but has developed an application for Habbo users to access their accounts via the Facebook website.

Totally agree. Found this nice web site whilst looking for a decent one to remark on. Effectively finished!

the converstation about the term ‘virtual world’ is kind of unimportant because the purpose of a game is not to see what it’s going to be called rather it is about the excitement of the game and the fun features it has, who cares if people call it a virtual world OR virtual enviroment, is it gonna kill somebody that its going to be called that. Anyway what are these responses supposed to be about? the terms used for these kind of games OR if they are good games worth playing? i am confused . maybe i need to find out what this website is all about . =)

Everyone loves what you guys tend to be up too. This sort of clever work and

exposure! Keep up the terrific works guys I’ve added you guys to my blogroll.